The reckless arc of nuclear waste accumulation and neglect is among the most profound oversights of democratic governance in the 20th and 21st centuries:

For decades, the United States aggressively pursued nuclear weapons and energy programs with no plan in place to manage the waste - widely recognized as the most dangerous material to exist on the earth.

With the advent of the first nuclear reactor in 1942, the geopolitical dynamics of the world were forever changed. The nuclear decimation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki followed only 3 years later. From 1951 to 1952, 100 atmospheric nuclear tests were detonated at the Nevada Test Site, with 921 additional tests detonated underground.

Despite the escalating arms race of the Cold War and fears of an apocalyptic nuclear winter, a new utopian promise emerged in nuclear energy - “Atoms for Peace” to fuel the world. For 40 years, as the military made more weapons of mass destruction, utility companies built dozens of commercial nuclear reactors. The US Department of Energy oversaw both programs but put no plan in place for the materials of unprecedented danger they created in the process. Institutionalized bravado, naiveté, and disregard led to a rapidly accelerating environmental crisis.

The lethal waste generated from these activities piled up across the country in aging facilities destined to decay long before the radioactive materials they contain. Nuclear waste had nowhere to go, until finally in 1982 Congress sketched out a plan: a permanent subterranean disposal site to entomb the nation’s growing stockpile of high-level radioactive waste. The Nuclear Waste Policy Act was passed and the Department of Energy was assigned the responsibility to identify and analyze candidate sites, and ultimately to make a recommendation to the president on the final site selection.

The plan would prove woefully flawed.

The six communities sitting atop the candidate sites were analyzed in excruciating detail - geology, ecology, hydrology, demography, soil composition, social conditions, regional economy, flora and fauna, and on and on.

Nine candidates in 6 states became five; five became three; and from those three, Yucca Mountain was chosen, on the unceded lands of the Western Shoshone Nation, 60 miles west of Las Vegas, on the western boundary of the Nevada Test Site.

Decades of blowback from local communities, activists, and politicians resulted in fierce public resistance, while the technical approach for containment within Yucca Mountain continued to shift, as DOE scientists and engineers learned more about water flow and infiltration within the mountain.

In 2010 Congress revoked funding for the Yucca Mountain Project, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission suspended its review before it could either approve or deny the licensing application.

Today, a nuclear renaissance is under way - driven by exploding energy demands for data and computation, and the trillion dollar modernization of the US Nuclear Arsenal - in a world embroiled by war. And still, no durable solution exists for dealing with the 90,000 tons of high-level radioactive waste, requiring isolation from human contact for 10,000 years, held for the time being in aging temporary facilities across 35 states.

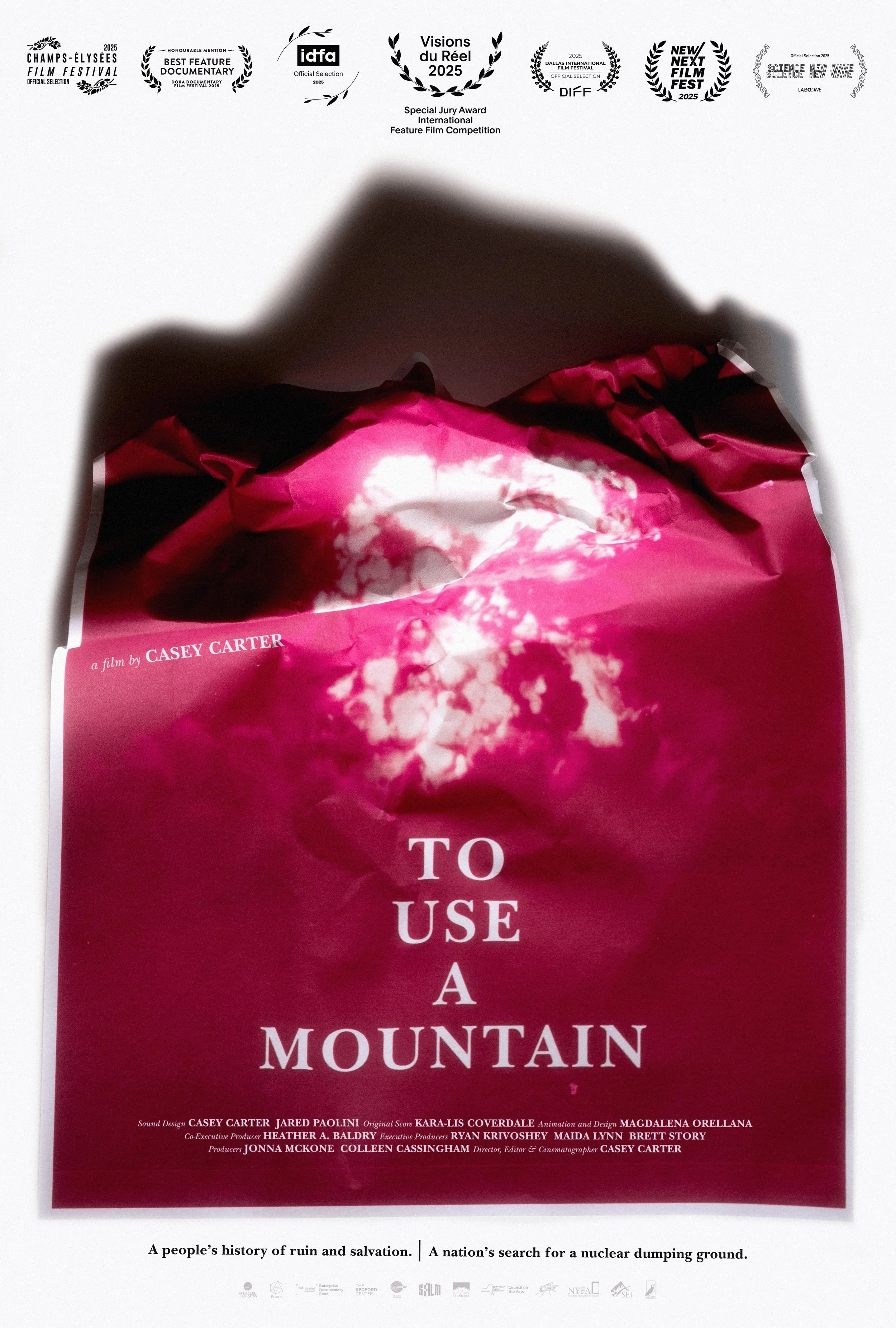

Southern Nevada Mojave Desert with DOE map overlay entitled “Community monitoring stations around the Nevada Test Site”